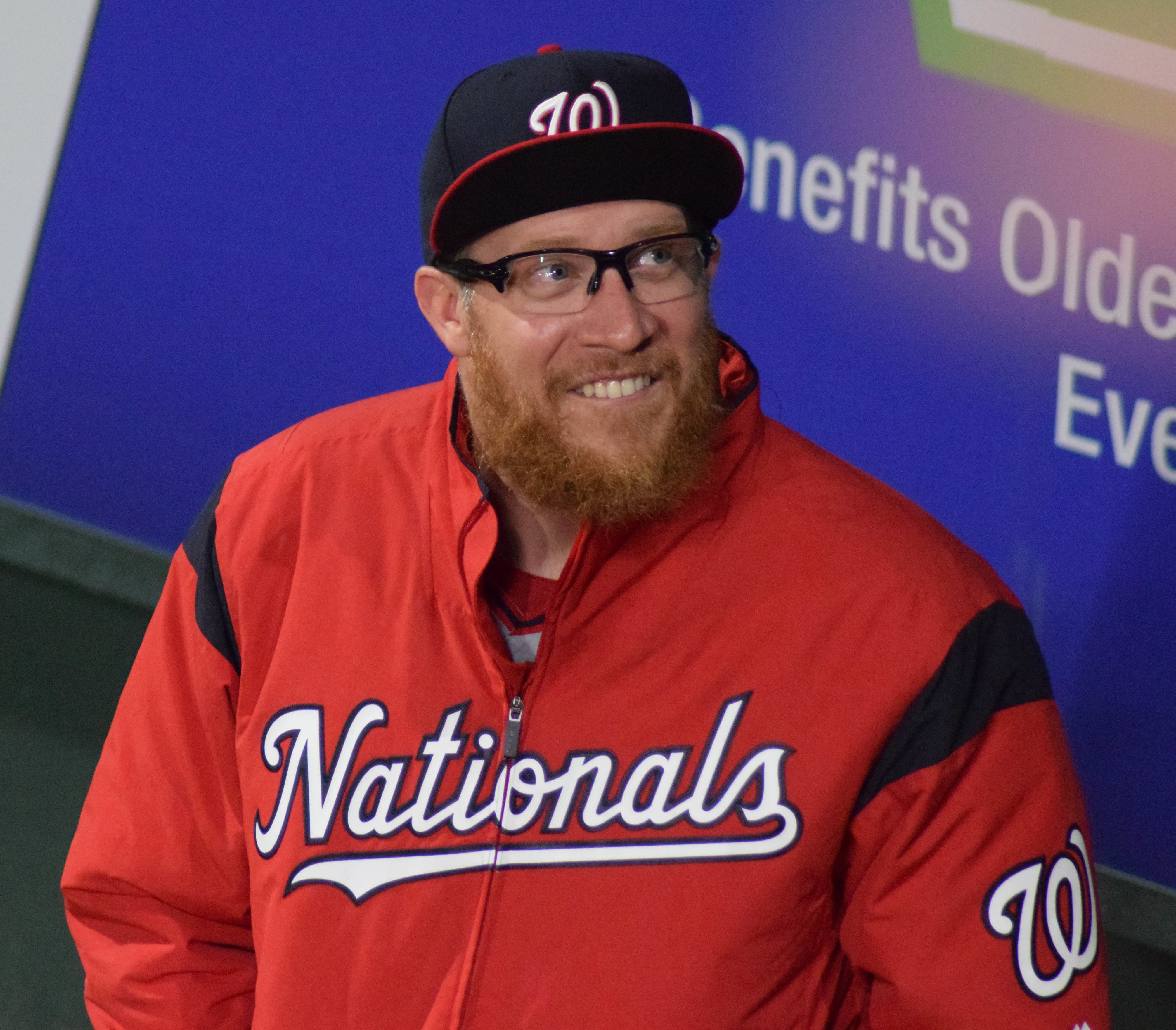

Washington Nationals closer Sean Doolittle was recently voted the “Good Guy Award” by the local media in the Baltimore and District of Columbia area.

But as I told MASN’s Mark Zuckerman via Twitter, he has everyone fooled.

Like the Wizard of Oz, all you have to do is pull back the curtain and you’ll discover someone who isn’t what he appears to be.

Doolittle and his wife, Eireann Dolan, are a politically astute, media savvy couple. They’ve spoken up on behalf of Syrian refugees, sponsored the Oakland Athletics’ first LGBT Pride Night and written opinion pieces about military veterans.

Doolittle recently appeared with CBS Sports’ Dana Jacobson to stress how important it is to read and to urge people to frequent independent bookstores. And earlier this Spring, he and Dolan protested New Era’s decision to close its Derby, New York factory – the facility where all the caps worn by Major League Baseball (MLB) players are manufactured.

“As players who continue to stand together it’s important that we also continue to stand in solidarity with the union labor that has helped make our game what it is today,” Doolittle tweeted at the time. “From the garment workers who make our uniforms to the stadium workers, vendors & security staff at our ballparks to the transportation workers who people rely on to get to games — their work makes our game possible. Baseball could not have grown into a [$10 billion] industry without them.”

Does Doolittle have a short-term memory problem? Conveniently, he forgets that baseball could not have grown into a $10 billion industry without the men who played before him, many of whom went to bat for the free agency today’s players now enjoy. Some of these men are without MLB pensions. But does Doolittle talk about this? Nope.

Because he comes across as such a standup guy, I’ve written that Doolittle should go to bat for the 626 men who do not get MLB pensions because they didn’t accrue four years of service credit, which was what ballplayers who played before 1980 needed to be eligible for the pension plan. Washington D.C. native Vince Colbert, 73, who attended Eastern Senior High School and who pitched for the Cleveland Indians, is among the men of color affected by this injustice. Former Washington Senators Dave Stenhouse, Marty Kutyna and Bill Denehy are also impacted by this moral indecency.

All the men without MLB pensions are in this position because, during the 1980 Memorial Day Weekend, a threatened players strike was averted when the league made the following offer to the Major League Baseball Players’ Association (MLBPA): going forward, every player would automatically qualify for a pension after 43 game days of service, and he’d qualify for health coverage after only one game day.

The problem for all the pre-1980 players who had more than 43 game days but less than four years was the proposal was never made retroactive.

According to the IRS, the maximum pension is $225,000 a year. But all the 626 men are receiving is $625 for every 43 game days they accrued on an active MLB roster, up to $10,000.

Very few sports columnists are writing about this injustice, which is more unseemly because the national pastime is doing very well financially. MLB recently announced that its revenue was up 325 percent from 1992 and that it has made $500 million since 2015. What’s more, the average value of each of the 30 clubs is up 19 percent from 2016, to $1.54 billion.

In addition, even though the current players’ pension and welfare fund is valued at $3.5 billion, MLBPA Executive Director Tony Clark has never commented about these non-vested retirees, many of whom are filing for bankruptcy at advanced ages, having banks foreclose on their homes and are so sickly and poor that they cannot afford adequate health care coverage.

As of 2016, Doolittle was earning a reported salary of $1.55 million. I mention that because many of the retired men who are without pensions stood on picket lines, went without paychecks and endured labor stoppages all so today’s players like Doolittle can command the monies they are making. The 25th man on the roster, for instance, was this season guaranteed a minimum salary of $535,000.

In 1966, the MLB minimum was just $6,000.

Doolittle’s Twitter handle is @whatwouldDOOdo. He’s got more than 98,500 followers who think well of him. But he’s dropped the ball on this issue.

That is because, when it comes to the retired players without MLB pensions, @whatwouldDOOdo apparently doesn’t want to do anything.

Douglas J. Gladstone is a freelance magazine writer and author of two books.

Author Profile

Latest entries

MLBDecember 14, 2022A Tale of Two Wyomingites

MLBDecember 14, 2022A Tale of Two Wyomingites MLBJuly 2, 2022Asking for Accountability From a POC Isn’t Bigotry

MLBJuly 2, 2022Asking for Accountability From a POC Isn’t Bigotry MLBFebruary 5, 2022A Valentine’s Appeal to Tony Clark, Executive Director, Major League Baseball Players’ Association

MLBFebruary 5, 2022A Valentine’s Appeal to Tony Clark, Executive Director, Major League Baseball Players’ Association MLBJanuary 19, 2022MLB: Pre-1980 Players Without a Pension List Now Stands at 525

MLBJanuary 19, 2022MLB: Pre-1980 Players Without a Pension List Now Stands at 525