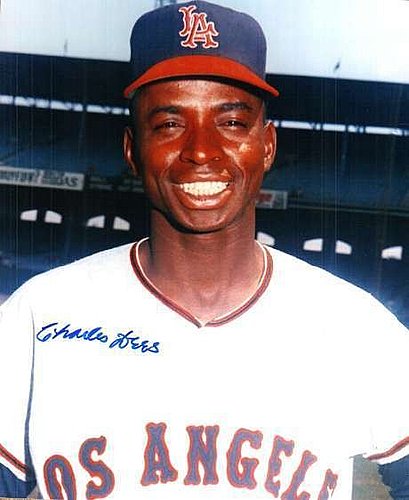

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Charlie Dees, who recently turned 86-years-old, was a first baseman for the California Angels for parts of three seasons, in 1963, 1964, and 1965; in 98 career games, he came up to bat 260 times and collected 69 hits.

Regrettably, Dees is among the 609 retired men not receiving Major League Baseball (MLB) pensions. Neither is Cottonton, Alabama native J.C. Hartman, 87, who played for the then Houston Colt .45s in 1962 and 1963. A shortstop who appeared in 90 career games, Hartman collected 44 hits in only 238 total plate appearances.

However, the number that I really want you to focus on is the $8,000 Dees made playing in 1964.

Neither Dees nor Hartman receive a pension because the rules for receiving MLB pensions changed over the 1980 Memorial Day Weekend. Both men, as well as the other 607, do not get pensions because they didn’t accrue four years of service credit. That was what ballplayers who played between 1947 – 1979 needed to be eligible for a pension.

Instead, effective April 2011, for every 43 game days of service these men accrued on an active MLB roster, they were awarded $625, up to the maximum amount of $10,000. And that payment is before taxes are taken out.

In a sport currently valued at nearly $11.5 billion, where the average big leaguer is earning $3.7 million a year, I find it unconscionable that all MLB and the union representing today’s players, the Major League Baseball Players’ Association (MLBPA) can dole out to these baseball old-timers is $625 for every 43 games they were on active MLB roster.

Many of these men walked the picket lines, endured labor stoppages, and went without paychecks so even the last man on the bench could earn $575,500 this past season.

And Dees and Hartman also lost valuable service credit because of the color of their skin. So, while the league in 2020 finally bestowed MLB status onto the Negro Leagues during the period 1920 to 1948, it doesn’t help Dees or Hartman one bit: Dees played for the Louisville Clippers of the Negro Leagues in 1957, while Hartman played for the Kansas City Monarchs in 1955.

It was the contributions of the men like Dees and Hartman that permitted Tuscaloosa’s great Tim Anderson to earn the $7.25 million he made last season playing for the Chicago White Sox. Yet anytime I have attempted to contact him about this injustice via his Twitter handle of @TimAnderson7, the All-Star shortstop has never gotten back to me.

Which I find peculiar. When the Players’ Alliance was formed two years ago, ostensibly to, as the group’s mission statement notes, “elevate racial equality and provide greater opportunities for the Black community,” Anderson was among the first to enlist.

I think it’s great today’s athletes are speaking out about social injustices. Since the confluence of athletic activism and sports is so important, I rejoiced when, this past summer, MLB made a 10-year commitment to the Alliance that includes $10 million a year, plus an additional $5 million in matching contributions.

But will Dees and Hartman get any?

My friend, Christopher Owens, whose father was the late United States Representative Major Owens of New York, recently told me that, if there’s one thing I should never do as a White guy, it’s presumed to tell a person of color, but especially a Black man or woman, what to think, say or do.

But I can wonder. So I wonder why so many of today’s baseball stars—both Black and White – aren’t trying to help the old-timers like Dees and Hartman.

Tim, if you can answer that question, I’d love to hear from you.

A freelance magazine writer, Douglas J. Gladstone is the author of A Bitter Cup of Coffee; How MLB & The Players’ Association Threw 874 Retirees a Curve.

Author Profile

Latest entries

MLBDecember 14, 2022A Tale of Two Wyomingites

MLBDecember 14, 2022A Tale of Two Wyomingites MLBJuly 2, 2022Asking for Accountability From a POC Isn’t Bigotry

MLBJuly 2, 2022Asking for Accountability From a POC Isn’t Bigotry MLBFebruary 5, 2022A Valentine’s Appeal to Tony Clark, Executive Director, Major League Baseball Players’ Association

MLBFebruary 5, 2022A Valentine’s Appeal to Tony Clark, Executive Director, Major League Baseball Players’ Association MLBJanuary 19, 2022MLB: Pre-1980 Players Without a Pension List Now Stands at 525

MLBJanuary 19, 2022MLB: Pre-1980 Players Without a Pension List Now Stands at 525